Mariinsky II (New Theatre)

| 10 December |

| 19:30 |

| 2021 | Friday |

|

Stars of the Stars Evening of one-act ballets: Carmen Suite. Marguerite and Armand. Ballet

|

|

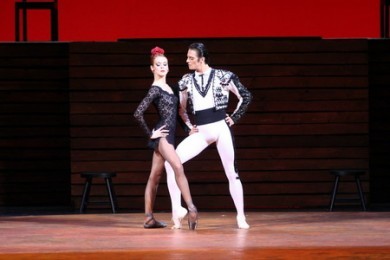

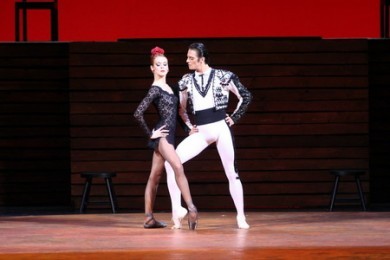

Carmen Suite

CREDITS

Music by Georges Bizet – Rodion Shchedrin Choreography by Alberto Alonso

Production Choreographer: Viktor Barykin

Production Designer: Boris Messerer

World premiere: 20 April 1967, Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow

Premiere at the Mariinsky Theatre: 19 April 2010

Running time: 45 minutes

At the heart of the ballet lies the tragic destiny of Carmen the gypsy girl and José the soldier who falls in love with her, though Carmen abandons him in favour of the young Torero. The relationships between the protagonists and Carmen’s death at José’s hands is predestined by Fate. Thus the story of Carmen (in comparison with the literary source and Bizet’s opera) is presented symbolically, which is reinforced by the unity of the setting of the plot (an arena which hosts a bullfight).

Violetta Mainietse

Marguerite and Armand

CREDITS

Music by Franz Liszt (Piano Sonata in B Minor)

Orchestrated by Dudley Simpson

Choreography by Frederick Ashton

Production Coach at the Mariinsky Theatre:

Set Designs and Costumes: Cecil Beaton

Original Lighting Concept: John B. Read

World premiere: 12 March 1963, The Royal Ballet of Great Britain, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London

Premiere at the Mariinsky Theatre: 8 July 2014

Running time: 30 minutes

The ballet Marguerite and Armand was created at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in 1963. Eye-witnesses recollect that following the premiere there were twenty-one curtain calls.

Frederick Ashton staged the ballet for Margot Fonteyn. Rudolf Nureyev, who had recently arrived in London, was all but unknown to Ashton at the time, but the charismatic young dancer’s partnership with the forty-three-year-old grande dame of British ballet – the incomparable Margot Fonteyn – provided a suitable theme for the production in which the choreographer was afforded the opportunity once again to present his darling in all her glory.

Ashton and Fonteyn emerged as great artists together – she as a ballerina and he as a choreographer. He created ballets with her in mind and dedicated them to her. And if Ashton had not had such a responsive performer who so inspired him over the course of more than a quarter of a century with her ease, emotionality and perfectionism his achievements in British choreography may well have been rather different. In the early 1960s Margot Fonteyn was planning to retire from performing and Ashton’s vision of a stage version of the story told by Alexandre Dumas fils in La Dame aux camélias happened to find resonance with her stage career. In the ballet, the heroine appeared at the end of her life’s journey: dying from consumption, she recalled moments of her former life and her passionate love. It suited Fonteyn to remember the past days of former artistic triumphs. And for Ashton this production was a deeply personal dedication. At the time, in spring 1963, no-one could have imagined that the method chosen to depict the story in the ballet would foretell the scenario of the ballerina’s own subsequent stage life, where events would not be regarded in retrospective but would look into the future. Her greatest triumphs were yet to come and her partnership with Nureyev was to be not a matter of nostalgia but rather the beginning of a new stage life.

Other amazing coincidences are connected with this production: having heard Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B Minor on the radio, Frederick Ashton considered it to be a suitable musical basis for his future ballet based on the plot of La Dame aux camélias. And how surprised he was when he discovered that Franz Liszt and Marie Duplessis, the prototype of Marguerite Gautier, the female protagonist of Dumas fils’ novel and stage play, were linked by a romantic relationship at the end of her short life and that the sonata was composed several years after her death!

Ashton did not create the ballet taking into account the individual characters of the performers, and neither did he tell a story about his dancers; he created their story – it was in this ballet that the legendary duo was born. This was why the choreographer categorically forbade any other dancers to touch this incredibly providential masterpiece. If, at first, during rehearsals Fonteyn and Nureyev had understudies, over time Ashton came to consider that the ballet Marguerite and Armand was not a vehicle where the performers could be replaced. The only possible content of the ballet was the personalities of its protagonists and the magnetism of their relationship on the stage.

But one by one the creators of the ballet all died – first Ashton in 1988, then Margot Fonteyn in 1991 and, two years after that, Nureyev. And the idea arose of reviving this “lost” wonder.

The first dancer with whom the guardians of Ashton’s legacy entrusted Fonteyn’s role was Sylvie Guillem, a ballerina with unique physical abilities and, which is more important here, a rare charisma and incredibly powerful individuality. In 1984 the nineteen-year-old Sylvie had been named an Étoile of the Opéra de Paris by Rudolf Nureyev, while some years later he took her to London for a co-performance and personally introduced her to Margot Fonteyn. Soon she became the brightest star of British ballet, as Fonteyn herself had once been, the unchallenged darling of London audiences. It is quite possible that she, more than anyone else, saw the obvious pointlessness of following the path taken by her mentor Rudolf Nureyev and his eternally adored Margot Fonteyn. Probably that is why Sylvie Guillem turned down the role on two occasions. And when she accepted it in 2000 she looked for the key to the image not in Fonteyn’s Marguerite but in the literary source.

Thus began the new stage life of Marguerite and Armand. The “ghosts” and destinies of Fonteyn and Nureyev have faded into the background, and today’s performers of the ballet – of whom there have been a great many since 2000 – dance the story of Dumas’ characters.

Olga Makarova

|

|

Mariinsky Theatre:

Mariinsky Theatre:  Mariinsky-2 (New Theatre):

Mariinsky-2 (New Theatre):  Mariinsky Concert Hall:

Mariinsky Concert Hall: