Main Stage

| 2 February |

| 19:30 |

| 2019 | Saturday |

|

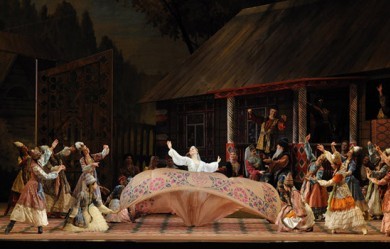

Shurale Ballet in 3 acts

|

|

| Artists |

Credits |

Piano Liydmila Sveshnikova Ballet company

Music by Farid Yarullin Tatiana Mashkova, Costume Designer Lev Milchin, Designer Alexander Ptushko, Designer Alexander Naumov, Lighting Designer Lyudmila Sveshnikova, Musical Preparation Batozhan Dashitsyrenov, Revival Designer

|

World premiere: Kirov Theatre of Opera and Ballet, Leningrad, USSR Premiere of this production: 28 May 1950 The performance has 2 intermissions Running time: 2 hours 45 minutes

Shurale is a revival of a well-known work that was premiered at the Mariinsky (Kirov) in the 1950s. A bright performance in generous and colourful scenery, arranged to the music based on oriental themes. Since the middle of last century, for decades, this ballet was among the most popular and beloved ones in the ballet repertory of the Mariinsky Theater. Over the last seasons, this performance have been carefully restored, and a number of young ballet artists of the Mariinsky Theatre took a great interest to learn the new for them style and roles of the main characters, enriched with a great drama, theatricality generous and sincerely expressive with respect to what is being called simple human feelings. Choreography by Leonid Yakobson features a combination of dance, drama and pantomime. It has a careful attitude to the era of storytelling and original details of plots. Revival of this ballet represents one of the most important periods in the development of the Mariinsky Ballet in the 20th century and its popularity these days proves that they have stood the test of time and now it is once again in the repertoire of the Mariinsky Theatre. Libretto by Ahmed Faizi and Leonid Yakobson after motifs from Tatar folk tales Full revival of the 1950 productionWorld premiere of the ballet Shurale: Tatar State Opera House, Kazan, 12 March 1945 World premiere of the second version of the ballet Shurale (under the title Ali-Batyr): Kirov Theatre of Opera and Ballet, Leningrad, 28 May 1950

On the two January Sundays at the Mariinsky Theatre we are presenting ballets choreographed by Leonid Yakobson: Shurale and Spartacus. Since the middle of last century, for decades, both performances were among the most popular and beloved ones in the ballet repertory of our theater. Over the last seasons, these performances have been carefully restored, and a number of young ballet artists of the Mariinsky Theatre took a great interest to learn the new for them style and roles of the main characters, enriched with a great drama, theatricality generous and sincerely expressive with respect to what is being called simple human feelings. Choreography by Leonid Yakobson features a combination of dance, drama and pantomime. It has a careful attitude to the era of storytelling and original details of plots. Revival of these ballets represents one of the most important periods in the development of the Mariinsky Ballet in the 20th century and their popularity these days proves that they have stood the test of time and now they are once again in the repertoire of the Mariinsky Theatre.

the return of the fairytale ballet Shurale

to the Mariinsky Theatre’s repertoire

to music by Tatar composer Farid Yarullin

and with choreography by the legendary Leonid Yakobson

The basis of the libretto comes from Tatar folk fairytales and the classical Tatar poet Gabdulla Tukai’s Shurale about the bird-maiden Syuimbike, the intrepid hunter Ali-Batyr and the evil Shurale (in Tatar mythology he is an evil wood spirit in the guise of a man with a horn on his forehead and long fingers.

The history of the ballet’s creation goes back to the 1930s. In 1934 the decision was made to found an opera and ballet theatre in Kazan. Immediately, the Tatar Opera Studio was set up at the Moscow Conservatoire, comprising student composers, among them the twenty-year-old Farid Yarullin. While still in Moscow, Yarullin began composing music on themes from fairytales and poems by Tukai. Shurale, a wood-goblin in Tatar folklore and a character in the eponymous poetic fairytale by Tukai, formed the focal point of the libretto written by the young man of letters Ahmed Faizi. Soon the ballet Shurale was included in the new theatre’s repertoire plan, and the premiere of the ballet was set for August 1941. Leonid Yakobson was dispatched to Kazan for work on the ballet having been appointed production choreographer of the first national Tatar ballet. Throwing himself into the task, the choreographer rewove the material the librettist had created. Rejecting the secondary plotlines, he picked out and intensified the main one, he dramatised the conflict and expanded the images of the protagonists. For Yarullin, these amendments signified a new round of work: he had to rework what had been written in a very short space of time and complete numerous new sections. To this day there are stories that for this purpose he was locked in a room in the Soviet Hotel, which he fled by shinning down a drainpipe. At last, by June the clavier manuscript was finished, but its full orchestration was delayed by the War. Composer Farid Yarullin died at the front in October 1943. In Kazan, the ballet was rehearsed for production and staged in March 1945, but with alternative choreography.

Yakobson was given the opportunity to complete the work he began, albeit in 1950, when the decision was taken to stage Shurale in Leningrad. A new version of the ballet was created for the Kirov Theatre: the libretto was completely reworked, and the score totally re-orchestrated (by Vladimir Vlasov and Vladimir Fere).

One year after the Leningrad premiere, Yakobson’s ballet received the State Prize, and five years after that it was transferred to the Bolshoi Theatre. In Leningrad the role of Syuimbike was danced by Alla Shelest, Natalia Dudinskaya and Inna Zubkovskaya, that of Ali-Batyr by Boris Bregvadze, Konstantin Sergeyev and Askold Makarov and that of Shurale by Igor Belsky and Robert Gerbek; later, in revivals in Moscow, the ballet dazzled with the presence of Maya Plisetskaya, Marina Kondratieva and Vladimir Vasiliev. In other cities and in productions by other choreographers, the ballet was staged over twenty times from the 50s to the 70s, but in the history of ballet it has gone down first and foremost as a work by Yakobson.

Among those rehearsing for the premiere are Yevgenia Obraztsova and Yekaterina Osmolkina (Syuimbike), Mikhail Lobukhin and Denis Matvienko (Ali-Batyr), Leonid Sarafanov, Alexander Sergeyev and Islom Baimuradov (Shurale) and other soloists of the ballet company. ABOUT THE PRODUCTION The story of the creation of the ballet Shurale dates back to the 1930s. At that time in the USSR, a new national policy was beginning to emerge. Each of the happy and free peoples of the Soviet Union were now obliged to have their own national culture to the utmost degree, constructed in the Moscow fashion. The mandatory set included classical music, opera and ballet. Special commissions were despatched to the republics – to select talents for whom Moscow and Leningrad academic institutions arranged national studios. By the late 30s, their graduates had travelled far to establish new companies. And to stage productions there, ballet-masters from the capitals were sent off: Fyodor Lopukhov, Kasian Goleizovsky, Vakhtang Chabukiani, Alexei Yermolaev... And Leonid Yakobson. All these choreographers were students of the classical school of the Imperial Ballet, they had gone through the trials and the experiments of the 20s. But the 20s they were forced to forget: now, in the USSR, a completely new art form was emerging, new grand ballet, in no sense Imperial, but fully imperialistic. And the classical language in it was general, like the party line.

At the time, Yakobson was also working in this dominant style – and yet he differed from the others. He was a secret admirer of Fokine, and it was not at all the Constructivism of the 20s that formed his youthful Weltanschauung. He was enthused by something else: the liberation of dance, the bright decorativeness, the expression of free movement, the unexpected and stunning verisimilitude inside conditionality and – of course! – other worlds, other cultures. Like Fokine himself, he was drawn first and foremost to visual imagery (and only secondly to musical structures), and like Fokine, he esteemed museums and found inspiration in them. And he was also a secret naturalist – in the sense that he knew how to imbue dance with something that he had perspicaciously seen in nature and in life.

The glory of empire, apart from anything else, was embodied in the ten-day arts festivals of the Soviet peoples in Moscow. At these grandiose displays and reports, new works were to be performed, “national in form and socialist in content”, where possible by representatives of the peoples themselves. In 1934 a decree was passed on the establishment of an opera and ballet theatre in Kazan. Immediately, the Tatar Opera Studio began work at the Moscow Conservatoire, including student composers – among them the twenty-year-old Farid Yarullin, who would go on two write Shurale. When they returned to their native land, the Tatar State Theatre of Opera and Ballet was opened (1939). The Principal Ballet Master was Gai Tagirov, who had trained in Moscow, and the Head of the Literature Department was the poet Musa Dzhalil. It is worth remembering the enthusiasm and pride that filled the new workforce of new national culture through the construction of this theatre and the first performances it gave! What now seems to us a normal campaign, a typical series of Stalinist propaganda, for them was the exultation of emergent hopes and the foundation for the emergence and elevation of a nation.

Back in Moscow, Farid Yarullin had begun work on themes from fairytales and poems by Gabdulla Tukai (1886–1913), the foremost national poet, whose significance for the Tatars may be compared to that of Pushkin for the Russians. Shurale, the woodgoblin of Tatar folklore and a character in Tukai’s fairytale poem, formed the core of the libretto, written for Yarullin by the young man of letters Ahmed Faizi. Soon the ballet Shurale was included in the repertoire plan of the new theatre – the more so as the festival of Tatar art was already planned: for August 1941. As soon as these dates were set, people from Leningrad were sent to Kazan: Pyotr Gusev was appointed Principal Choreographer of the festival and the Stage Director of the first national ballet was Leonid Yakobson.

Once in Kazan, Yakobson, temperamental and implacable, first of all fell upon the libretto. Turning to a Tatar theme opened up to him the door of Fokine’s way of thinking about an exotic and ancient culture; it was this, and not the staging of specific fairytales, that was his task – Yakobson thought in categories that were much greater. And he authoritatively sewed together the fabric conceived by Ahmed Faizi. Disregarding secondary plot lines, he focused on and heightened the main one, he dramatised the conflict, he rounded out the images of the main characters, and the title role, which with Tukai was a somewhat silly creature, he adorned with ominous, demonic traits. And Yakobson, abandoning the details so dear to the author in the original source, brought the libretto into a state of theatrical believability and ballet’s traditions. For Yarullin, there transmutations signified a new twist in the work: quickly he had to process what had been written and complete many new sections. The tales were retained, even though for the purpose of completing his work he was locked in a room in the Soviet Hotel, which he fled by shinning down a drainpipe! At last the manuscript score was complete – but it was now June 1941. In the future, the destinies of the young representatives of Tatar culture working on the production of Shurale would no longer be linked with the ballet. The composer Farid Yarullin died at the Front in October 1943. And Head of Literature Musa Dzhalil was executed in a Berlin prison in 1944.

With regard to the ballet, it was nonetheless rehearsed and performed in March 1945. Yarullin’s manuscript was orchestrated by Moscow composer Vitachek, and the dances staged by Zhukov, a fellow Muscovite, together with Tagirov.

However, Shurale had another, broader destiny, and this was linked not to the Kazan theatre but to Leonid Yakobson. The possibility of completing work already begun came to Yakobson in 1950, when it was decided to stage Shurale in Leningrad. For the Kirov Theatre (originally and once again the Mariinsky) a new version of the ballet was created: the libretto was completely reworked, and the score totally re-orchestrated (by Vladimir Vlasov and Vladimir Fere). Now the music went far beyond the creator’s original idea, while at the same time coming much closer to the choreographer’s plan: everyday life ceded to a heroically romantic feel, and the Tatar folklore appeared more generalised and poeticised. As a result, in the Leningrad production instead of the touching folk openness we see monumentality, and instead of local significance it is on the scale of the capital and the scale of Art. And the new name – Ali-Batyr – after the Russified name of the hero. However, the original name was soon restored to the Tatar ballet: at the insistence of Faizi and Yarullin’s widow.

And so Shurale became a full, “grand ballet” that answered the call of the time and the social demands. Apropos, it had something that differentiated it from other works of a similar kind – and here it is not so much the specific nature of the material as it is the particular detail of Yakobson’s choreographic thinking. The main quality of Yakobson’s vision is the sharpness, the main quality of Yakobson’s dance material the intense inner energy, the inexhaustible inner pressure and tense nerve. In terms of his temperament, Yakobson was frenzied, “wild” – in the sense that French Fauvist artists called themselves “wild”. And at the same time he was extremely artistic as well as extremely refined and sophisticated. Only he can interpret classical pas with such stunning explicitness, not giving in, moreover, to illustrativeness. Only he can thus poeticise a folkloric ritual, while not becoming and ethnographic historian. Only he can thus lay open the characters, while not ruining the sheer dance fabric. Only he, ultimately, can be so wonderfully and so convincingly animalistic. His Shurale is a thin, long, slippery animal; his bird-maidens are not a metaphor as they are in Swan Lake, but real, small and swift birds, with fluttering wings – while the plastique theme of the arms, as we learn in the next act, is taken from a folkloric dance. We should also add that in Shurale we can already make out the form of the choreographic miniature which Yakobson would later go on to develop more fully: the dances of the gossips (later Yakobson would stage a separate dance number under this name), the matchmaking men and women, and Shurale himself, so full of weight, so voluminous, so exhausting that he could truly be sufficient in himself.

One year after the Leningrad premiere, Yakobson’s ballet received the State Prize, and five years after that it was transferred to the Bolshoi Theatre. In other cities and in productions by other choreographers, the ballet was staged over twenty times from the 50s to the 70s, but in the history of ballet it has gone down first and foremost as a work by Yakobson.

Inna Sklyarevskaya

SynopsisAct I

In a dense forest, the evil master of the woods Shurale is inside the trunk of a tree. Ali-Batyr, a young hunter, appears in the forest clearing. Seeing a bird fly past, he seizes his bow and arrow and sets off after the bird. Shurale emerges from his lair. All the wood spirits that he rules awake. Genies, witches and evil spirits entertain their master with dances.

As the sun begins to rise, the evil spirits hide. A flock of birds comes down on the clearing. They spread their wings and transform into young maidens. The girls frolic through the forest. The last to abandon her wings, the beautiful Syuimbike follows them into the woods. Shurale, keeping an eye on her from behind a tree, steals the wings and drags them back to his lair.

The girls emerge from the woods. They perform merry round dances in the clearing. Unexpectedly, Shurale jumps out at them from behind the tree. Startled and frightened, the girls pick up their wings and, transformed into birds, take to the skies. Only Syuimbike is left to wander around, having been unable to find her wings. Shurale orders the evil spirits to surround the girl. She is a prisoner and terrified. Shurale is prepared to celebrate his victory, but Batyr and rushes out from the forest and hurries to Syuimbike’s assistance. The furious Shurale wishes to strangle Batyr, but the youth knocks the monster down to the ground with one powerful blow.

In vain, Syuimbike and her saviour look for the wings everywhere. Tired of the fruitless search, in torment Syuimbike drops to the ground and falls asleep. Batyr carefully picks up the sleeping bird-maiden and leaves with her.

The defeated Shurale threatens Batyr with a pitiless revenge for having kidnapped the bird-maiden from him. Act II

Batyr’s courtyard. All the fellow-villagers have come to a banquet in honour of Batyr and the beautiful Syuimbike. The guests make merry and the children romp around. The bride alone is sad. Syuimbike is unable to forget her lost wings. Batyr tries to distract the girl from her gloomy thoughts. But neither the Dzhigits’ dances nor the maidens’ round dances bring any cheer to Syuimbike.

The celebration ends. The guests depart. Unnoticed by anyone, Shurale slips into the courtyard. Seizing a suitable moment, he throws Syuimbike her wings. In delight, the girl hugs them to her breast and wants to fly off, but in indecision she stops: she would be saddened to abandon her saviour. But the desire to take to the skies is stronger. Syuimbike takes to the air in flight.

Immediately she is surrounded by a flock of carrion crows sent by Shurale. The bird makes a bid for freedom, but the carrion-crows force her to fly towards the lair of their master.

Batyr enters the courtyard. He sees the poor bird flying away in the sky, beating her wings inside the circle of black crows. Seizing an incandescent torch, Batyr follows in pursuit. Act III

Shurale’s lair. Here the bird-maiden is languishing in captivity. But Shurale cannot break Syuimbike’s iron will and the girl rebuffs his advances. In fury, Shurale wishes to give her to the evil wood spirits to be torn to pieces.

At this instant, Batyr runs onto the clearing with a flaming torch in his hand. At Shurale’s demand, all the witches, genies and Shurale’s minions attack the youth. Batyr then sets light to Shurale’s lair. The evil spirits and Shurale perish in the fiery flames.

Batyr and Syuimbike are alone amidst the storming inferno. Batyr hands the maiden her wings – the only way to salvation. But Syuimbike does not wish to abandon her beloved. She throws her wings into the flames – let them both perish in fire. Then the forest fire suddenly dies away. Free of the evil spirits, the forest is miraculously transformed. Batyr’s parents and the two matchmakers appear. They wish happiness to the groom and his bride. |

|

Mariinsky Theatre:

Mariinsky Theatre:  Mariinsky-2 (New Theatre):

Mariinsky-2 (New Theatre):  Mariinsky Concert Hall:

Mariinsky Concert Hall: